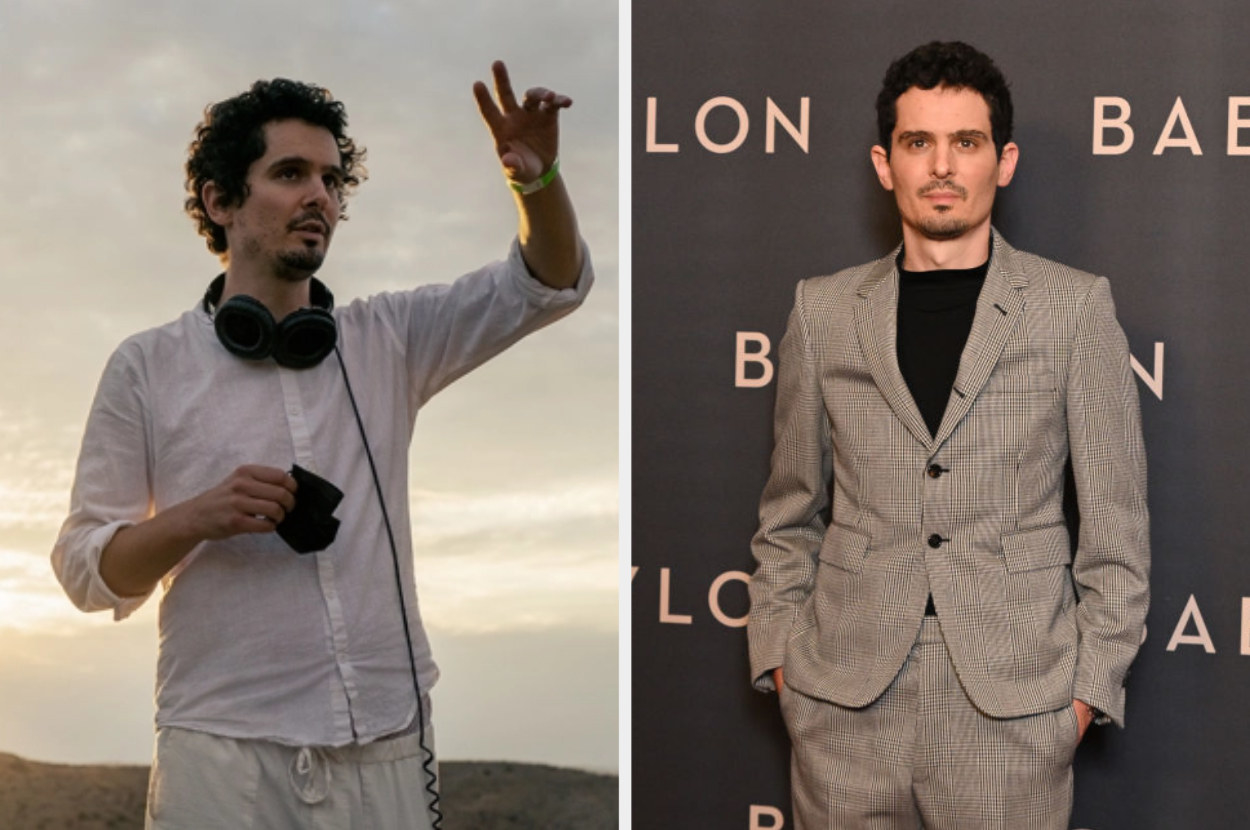

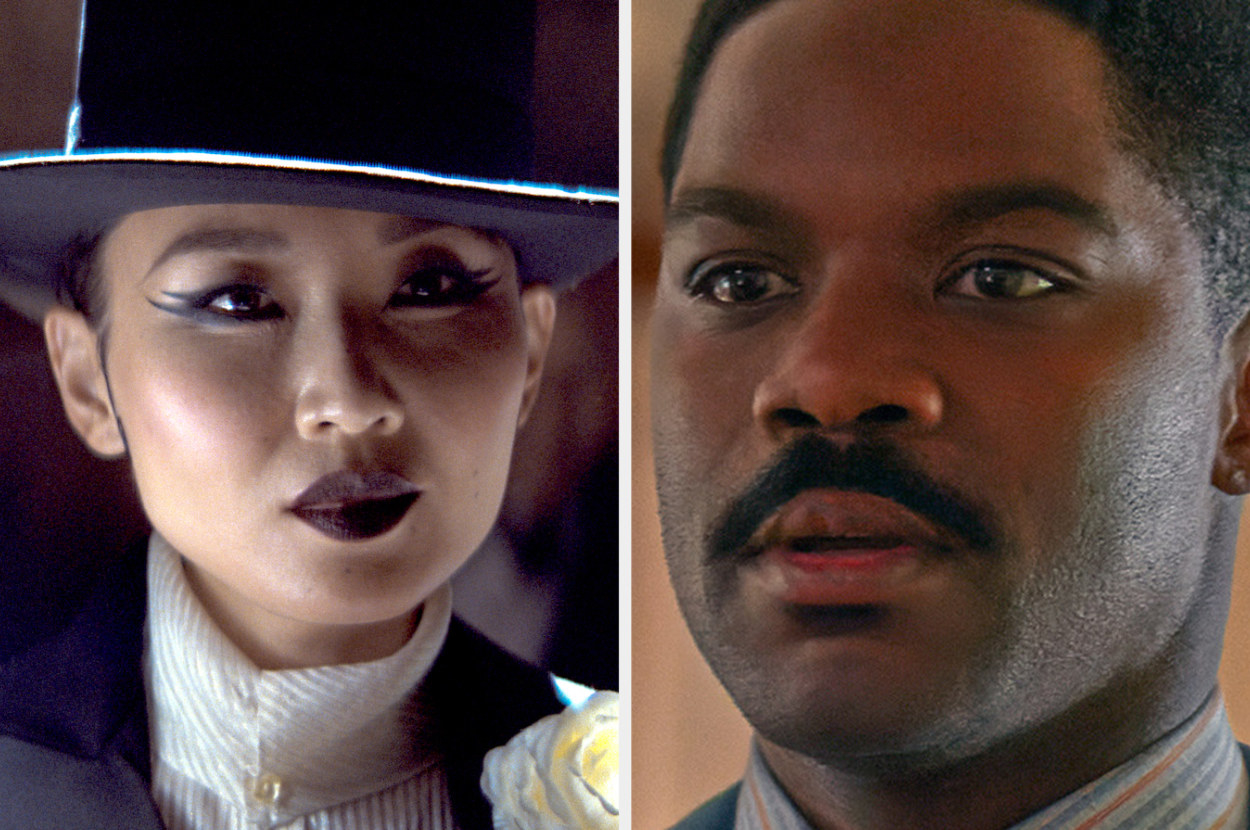

Brad: I’m gonna jump in here! I think this discussion about length is kind of misleading, I think what it’s really about is – does it play, or does it not? I know there was an attempt to cut down the film, I saw a shorter version and it felt longer. This was the version that worked. It had a percussion to it and a rhythm that felt right to me. I mean, it’s such a sprawling epic and you follow all of these characters through this revolutionary time in film history. But I’m gonna let you talk about your movie now… Damien: No, no, you said it. I think time does become your own perception of it in a movie, which is what’s fascinating about them. There were shorter cuts and longer cuts, and it was about finding that perfect balance where you feel the scope of it, and you’re actually able to live with these characters. Brad’s character, for example, progresses a lot and goes through a pretty big change. The world of the movie goes through a pretty big change, and I wanted to capture that but still make it feel snappy. Damien: Yeah, I’d say there was a composite of people who influenced every character. There’s an actor named John Gilbert who inspired Brad’s character, but there’s also a little of Douglas Fairbanks in there too. There’s a lot of Clara Bow in Margot’s character; everyone gestures to a real person, or two, or three. And Brad, did anything or anyone inform the way you played your character? Brad: Well, the alcoholic part I drew from Clooney, hands down, no question. And then all the good stuff, I pretty much had that naturally. No, it’s a strange thing to play something you’re familiar with, but it’s in another eco-system and vernacular. What I really appreciate about this movie is that Damien was intent on not doing a stodgy period piece, but capturing that “Wild Wild West” idea of Hollywood at the time, according to reports. We considered things that would be shocking today. Like in Gone With The Wind when Rhett Butler said, “frankly, my dear, I don’t give a damn”, that was like “huhhhh”! (gestures in shock). But today that wouldn’t mean anything. Damien: Brad did adlib a pretty great variation on that Rhett Butler line. Brad: I can’t believe that made it in! Damien: How could it not? Brad: I was actually really moved by it. Not necessarily because of a singular performer, but because I could feel the lineage; I felt like I was a part of a story, y’know? You have this little bit that you offer and it goes on for however long. I get really moved by that. And were you shocked by your character’s ending? Brad: Poor Damien, man. We were supposed to film this a year before we did, but then lockdown happened, and I spent that year and a half just talking to him about the ending! Damien: I’ll say this, I didn’t mind Brad sending me all his ideas. If they’re coming from someone with good ideas like Mr. Pitt here– Brad: Apparently not! There was a year and a half of them just to come around full circle to where we started. Damien: Okay, so the ending is where we started, but there was a build-up to it, and it was very different in early drafts of the script. In retrospect, that original version short-changed the nuance of the role. So just through conversations with Brad, the new ending ended up being so much richer. To me, it’s my favourite stretch in the movie, it’s the one that touches and moves me the most. I don’t think it would have been without Brad annoying me with his ideas. Brad: Not that much, but there was a four hour version of this, right? Which is not odd. Damien: The irony is that the first somewhat polished cut of the movie was shorter than the current movie – it was like two hours fifty minutes or something. Looking back, I think it was too short; I felt certain key things had been left on the table. Then the next cut was too long. Eventually, we found that kind of accordion between those two poles, which was the sweet spot. Brad: Things do have to get sacrificed for the rhythm of a film. It’s amazing how you can chuck a scene and things can just grind to a halt. Editing is a real art form, and I really film like Tom Cross – our editor – and Damien found the sweet spot here. Brad: Yeah, was that difficult? Cos it looked like it! Damien: It wouldn’t say it was easy, but it was really fun; I felt like a kid in a candy shop. It’s like Orson Welles said, “it’s the biggest and best toy train set that a boy could ask for”. But then you’re also losing your mind and pulling your hair out. And Brad, what was it like working with Damien? Any standout memories? Brad: (puts his arm around Damien) He’s just very tender and caring. Nah, listen, I was pretty mesmerised to see how he orchestrated all of this, and there was an energy to it on set that I rarely get to experience. This guy came on the scene with Whiplash and got everyone’s attention. He really brings something new and fresh to filmmaking. It’s no mystery to me why he’s the youngest director to win an Oscar… I think that’s right? This is only his fourth film, but he’s four for four in my book. Damien: It was less schematic than that. One thing that really interests me about this time period is that counter to what you’d expect – considering the “progress” of Hollywood – this early period was more diverse than the few decades that followed. I think a lot of that speaks to the sort of unregulated, “Wild Wild West” freedom that existed in Hollywood early on. Different kinds of people wore different hats, and suddenly sound comes in, certain moral codes come in, and it becomes more of an industry. So a lot of that excitement gets funnelled away, and you have to jump ahead 40, 50 years to find any kernels of that sort of freedom coming back.